Rondo tackles industrial heat to drop global CO2 emissions by 1% in the next decade

In climate circles we spend a lot of time talking about manufacturing and power generation in the effort of cutting CO2 emissions. It’s pretty rare that I get a whiff of a company that has a clear path toward cutting global carbon emissions by a full percent — but that’s what Rondo Energy pitched to […]

In climate circles we spend a lot of time talking about manufacturing and power generation in the effort of cutting CO2 emissions. It’s pretty rare that I get a whiff of a company that has a clear path toward cutting global carbon emissions by a full percent — but that’s what Rondo Energy pitched to its investors and customers, raising $22 million and setting some very excited environmentalists’ hearts a-flutter in the process.

The company’s pitch is pretty straightforward: Industry uses a god-awful amount of heat, which typically used to be delivered through natural gas. Over the past decade, something very interesting happened; as carbon credits and the price of natural gas increased, heat-hungry industries started looking around for other options. These industries include food processing, oil production, cement manufacturing, hydrogen generation and raw material refining. As prices started creeping up, the cost of renewable power — solar and wind, primarily — started plummeting. In some parts of California, this has gotten so extreme that during parts of the day, generation outpaces demand and the grid’s capacity to absorb it all by quite a bit. The result is that there are parts of the day where electricity is so cheap it may as well be free — but it has nowhere to go.

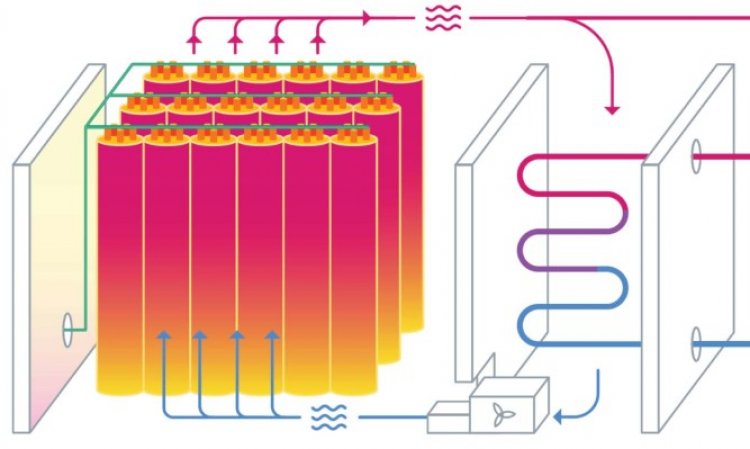

Rondo Energy to the rescue. It has developed a new way to store all that power; not in the form of electricity, but in the form of heat. Heat has the benefit of being extremely fast — you don’t have to worry about the speed that a Lithium battery can absorb electricity. Essentially, you just throw the electricity through a massive resistor, which heats up to ridiculous temperatures. Now all you need to do is to capture the heat for later.

“If you put brick in your oven, and heat it up. It stays hot for a long time., explains John O’Donnell, the CEO at Rondo Energy, simplifying the company’s tech to a level that a five-year-old (and, for that matter, an under-caffeinated 40-year-old tech journalist) can firmly grasp. He assures me that the actual storage isn’t much more complex than the bricks, but that the magic of the tech is in the shape of the “bricks” and the AI-powered control systems that heat the materials and deal with the extraction when the industrial customers need the heat again.

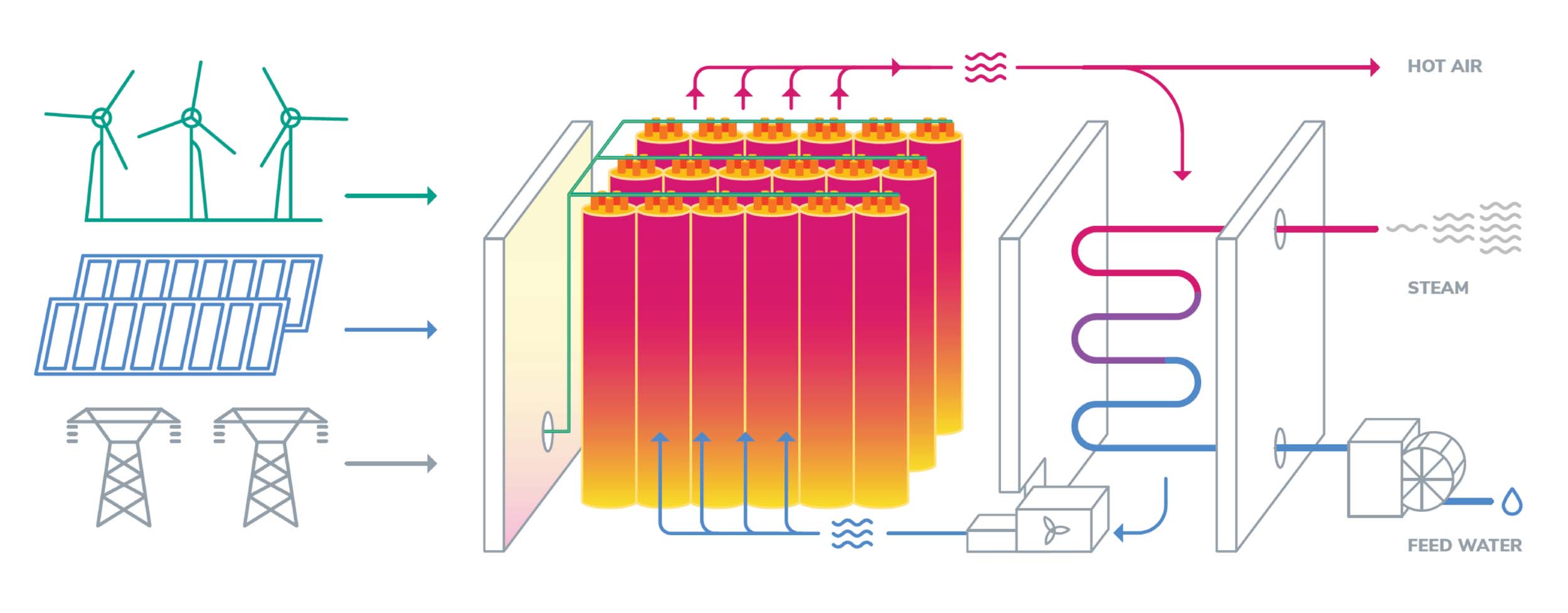

“We’re storing heat as very high-temperature energy in solid materials. The truth is, my coffee thermos holds more energy than a laptop battery, a lot more cheaply. For the heating — there’s no magic there: your toaster and hairdryer uses the same technology for generating heat as we do. We developed a new combination of materials for the storage. You can then deliver heat continually by circulating air into the stack of that material and getting superheated air out,” explains O’Donnell. “Then we either turn that heat into steam in a conventional boiler or we deliver directly to users with high-temperature needs, such as making glass or cement. This is a technology that operates at a small fraction of the cost of an electrochemical battery and maybe more significantly, roughly twice the efficiency and half the cost of any hydrogen system.”

Take excess electricity. Build the world’s biggest hair dryer and aim it at a pile of bricks. Then when you need the heat, send air through the bricks. Slightly simpified, obviously, but some of the best ideas are, essentially, that simple. Illustration: Rondo Energy

The hydrogen comparison is significant, because for the longest time, the only option that was available in the market was to take the electricity and generate hydrogen. When the power was needed again, you could burn the hydrogen. The issue, O’Donnell claims, is that the efficiency of these systems is 50%, at best. Rondo’s system, in comparison, claims it reaches 98% efficiency, with systems that are orders of magnitude simpler than battery or hydrogen storage.

This is significant, because the industrial needs for heat are vast — Rondo’s home state of California burns more natural gas for industrial heat today than it burns for electric power; as the economy equation shifts and heat storage of excess natural electricity becomes more viable, that could have a tremendous impact on decarbonization. Globally, around 36% of greenhouse gasses come from industry, so being able to drastically reduce — and eliminate the need to do carbon-capture from gas-powered heat — could have a tremendous impact.

“Our innovation is a combination of the physical storage materials and AI supervision of the controls. A lot of things are possible today that weren’t possible 10 years ago. What we are doing today would have been stupid five years ago — when electricity was more expensive, you’d never dream of doing this,” laughs O’Donnell. “But it’s very clear that we are on a trajectory that could become a major part of industrial heat. We see 1% reductions in whole-world emissions in the next decade.”

It’s possible to store temperature in liquid salt at around 570°C (1,050°F), which Rondo’s CEO claims is the nearest competitor that’s able to do heat storage at similar scale as its temperature batteries. Rondo, however, is able to store heat at 1,200°C (2,200°F) — which is far closer to the needs of industrial and manufacturing heat applications.

The company raised a $22 million series A from Breakthrough Energy Ventures and Energy Impact Partners. This funding enables Rondo Energy to begin manufacturing and delivering customer systems later this year.

“We believe the Rondo Heat Battery will prove critical to closing stubborn emissions gaps,” said Carmichael Roberts at Breakthrough Energy Ventures. “The cost of renewable energy has been steadily falling, but it hasn’t been an option for industries that require high-temperature process heat since there was no way to efficiently convert renewable electricity to high-temperature thermal energy.”

Of course, Rondo’s bet only makes sense if the trends continue in the direction they are going. If fusion power suddenly becomes plentiful and available, that might replace the need for this type of energy storage for industry. Similarly, it’s likely that other industries are also eyeing the super-cheap mid-day electricity provided by the excess solar power, so eventually, demand will be driven up there, too. Having said that, it’s a little while since we’ve seen a truly innovative way of storing vast amounts of energy at high speed, and the planet needs a carbon break. For now, it seems like Rondo Energy has found itself a win-win solution: High-temperature industries get cheap heat, investors are salivating over the possibility of a rapid return on investment and any solution that has a reasonable chance at decimating our carbon output is worth investing in, in my book.