Steal this hot new summer look (it’s bacteria)

Bacterial secretions might dye your future wardrobe, and that’d be an improvement. That’s because textiles usually get their hues from toxic chemicals, and the resulting wastewater—laden with dyes, acids and formaldehyde—destroys rivers, such as those surrounding Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. Wastewater treatment, when it happens, is just one of the energy-intensive (read: carbon-spewing) […]

Bacterial secretions might dye your future wardrobe, and that’d be an improvement.

That’s because textiles usually get their hues from toxic chemicals, and the resulting wastewater—laden with dyes, acids and formaldehyde—destroys rivers, such as those surrounding Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. Wastewater treatment, when it happens, is just one of the energy-intensive (read: carbon-spewing) processes that make fast fashion possible.

The environmental crises linked to textiles have given rise to several firms that aim to reimagine dyeing altogether. One such company, Colorifix, just got a boost via a $22.6 million (£18 million) series B round, led by Swedish fashion giant H&M.

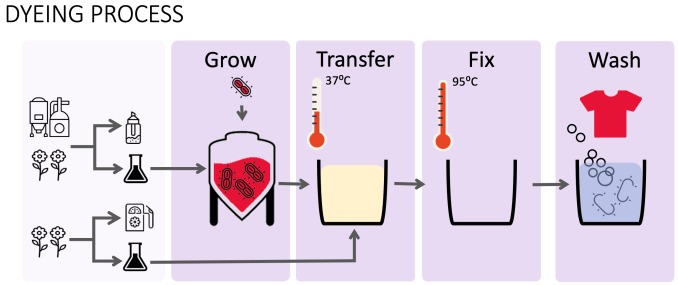

Colorifix stands out for its progress in using microbes (such as E. coli) to naturally deposit dyes directly onto fabrics. Its microorganisms are engineered to produce specific colors and then brewed in vats like beer.

A third-party life cycle analysis (paid for by Colorifix) found its dyes use at least 49% less water and 35% less electricity than conventional cotton dyeing processes, apparently slashing carbon emissions by 31%. That’s for natural fibers, but the upsides are greater for materials like polyester or nylon, which are generally made from petroleum and trickier to dye. “If you go to synthetics, we’re going to save way more than this,” cofounder and chief scientific officer Jim Ajioka added in a call with TechCrunch.

So, uh, how does one persuade microbes to make dyes? I asked Ajioka, and he told me to check my shower for something red.

“In a place like England, you’re gonna get mold, mildew and stuff growing on the tiles. And you’ll see red bacteria [known as Serratia marcescens]. They secrete that color onto your tiles or your grout” he explained. “That’s what we do.”

But to produce specific colors, Colorifix says it starts by identifying a specific color in nature, like a green hue found on a parrot’s feather. The company then taps online DNA databases to “pinpoint the exact genes that lead to the production of that pigment.” From there, Colorifix builds the DNA and inserts it into a small group of bacteria or yeast cells. Within a day they replicate millions of times over on a petri dish. “The resulting engineered microbe then acts as a tiny biological factory,” the startup said in a statement, ultimately producing dyes that stick to natural and synthetic materials.

How Colorifix dyes textiles with bacteria.

Zooming out, the fashion industry consumes an enormous, basically unimaginable amount of water. A 2014 World Bank report found the industry goes through about 9 billion cubic meters of water per year—roughly five and a half times more than what New York City consumes in the same period. Next to the images of Dhaka’s mutilated rivers, it’s possible the concept of dunking t-shirts into a bacterial soup suddenly seems more palatable. But if you still find the idea of microbes swimming with your clothes a little off-putting, you’re not alone. I did at first, and when I said as much to Ajioka, he gave me a mouthful.

Following the dyeing process, Ajioka explained, “yeah, you have to put it through the wash. But, you know, you wash your clothes all the time. Think about the number of bacteria that are on your t-shirt right now. It’s disgusting,” he said, directing his comments at my shirt specifically. Then came the questions. “Think about it. How do you wash your clothes? What does laundry detergent do? It gets rid of proteins, carbohydrates, and, fats and oils and stuff, right? That’s what it’s made to do, and what do you think microorganisms are made of? That’s why your clothes don’t stink after you wash them,” he added.

Cleanliness aside, Colorifix is not the only firm aiming to develop cost-effective, bacteria-produced dyes to curb pollution. It’s joined by Paris-based Pili and Vienna Textile Lab. So far, none of these companies have brought the idea into mass production, making bacteria-dyed clothes hard—but not impossible—to come by.

In December 2021, Colorifix dyes were used to produce a limited run of Pangaia tracksuits in two soft hues, dubbed blue cocoon and midway geyser pink. Just the former color was still available when this story was published, as either a $170 hoodie or $140 pants. Earlier, Colorifix dyes were used to make a Stella McCartney dress, which was exhibited at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 2018.

In other words, eco hypebeasts: good luck.

Colorifix-dyed hoodie designed by Pangaia

Beyond microbes, other businesses aiming to crack sustainable dyes include Alchemie, a Cambridge, U.K.-based company that claims to have developed a waterless dyeing process; DyeCoo, a Dutch firm that dyes fabrics via pressurized CO2; and New York-based ColorZen, which makes a cotton pre-dyeing treatment that apparently slashes water use and eliminates the need for salts.

Along with H&M, investors such as Sagana, Cambridge Enterprise and Regeneration.VC also chipped in on Colorifix’s series B round. With the new cash, the startup said it will triple the size of its team to about 120 staffers as it prepares to move its tech “into the supply chains of several leading players in the global fashion industry.” The company declined to share more when asked how long I’ll have to wait to buy a microbially dyed tee of my very own.