Early-stage fundraising is a tale of two planets

For every story I hear about a huge round that came together in two weeks, I meet 20 great founders who hustle for months and can’t raise a penny.

If you follow mainstream tech media, you could be forgiven for thinking that venture capital is a founders’ market today after two years of record round sizes and outcomes.

There is some truth to this: VC had its biggest year in 2021, more than doubling from 2020, which was already a record year for investments. Almost 400 new companies surpassed a $1 billion valuation in 2021, increasing total unicorn count by 69% in just a year.

Stories abound of massive rounds materializing quickly for companies at even the earliest stages. Wing VC, which tracks financings by Silicon Valley’s most “elite” VC funds, reports that the median Series A financing by these firms grew by 38%, and corresponding pre-money valuation by 71%, both off previous record highs recorded in 2020.

But hidden under the headlines is another story: Higher valuations are accompanied by a much larger variance among companies. As Hustle Fund’s Elizabeth Yin tweeted recently, round sizes and valuations haven’t grown for all companies across the board; rather, they have bifurcated.

This tracks with my experience investing in companies founded by women, most of whom were first-time founders and disconnected from mainstream VC. For every story I hear about a huge round that came together in two weeks, I meet 20 great founders who hustle for months and can’t raise a penny.

A fund known for leading huge rounds in pre-revenue, pre-launch, pre-everything companies told a founder in my portfolio that they want to see her reach $1M+ annualized revenue before considering her pre-seed.

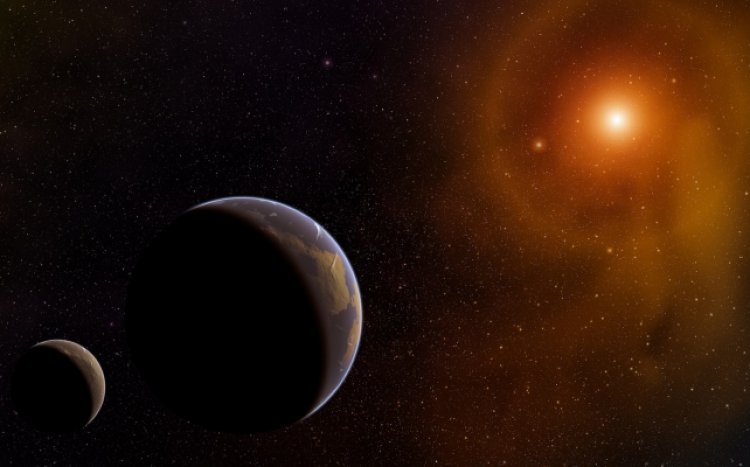

The experience among founders varies so greatly, they might as well be living on different planets. Founders who are experienced, pedigreed, smooth or well connected — or some combination of these — live in a planet of big, buzzy, competitive early rounds, which we’ll call “Planet Flush.”

Founders who are outsiders, don’t generally fit the pattern and are not connected to sources of capital live in a planet where fundraising is extremely difficult and unlikely, necessitating very scrappy execution to even get a chance to grow. Let’s call this one “Planet Scrappy.”

At the risk of stating the obvious, investor behavior is completely different in Planet Flush and Planet Scrappy. In Planet Flush, at the earliest stages when there’s no tangible traction to evaluate, investors are comfortable making a bet on the size of the market and the perceived caliber of the founders.